As in most years, I find myself in reflection mode the closer we inch toward the holidays, and this year is no different. The latter part of 2015 has been filled simultaneously with some of my highest highs and lowest lows, which is why I’ve been fairly quiet lately. Frankly, there’s been a lot going on that has taken precedence over this blog, and I feel that all of us deserve time to take stock of what’s important in life in order to be the best people we can be.

That said, I’ve still been spending a good amount of time thinking about our built environment. Pretty much every trip I’ve made outside the house has been an opportunity to consider what makes our neighborhood special and what can be improved in order to allow it to function better for the people who live here.

To close out 2015 at Main Street Beverly, I’d like to share some thoughts about what I’m thankful for in the 19th Ward and what I would love to see in the coming year (all focused on urbanism, of course).

I’m thankful for…

Our good bones. Possibly our neighborhood’s greatest asset, one that drew me and likely many others here, is the fact that it was laid out in an era before planners began overcompensating for personal automobile use. Unlike many areas on the edges of other major U.S. cities, Beverly, Morgan Park and Mount Greenwood feel more like traditional neighborhoods rather than sprawling suburbs. We have a strong street grid that accommodates pedestrians, bicyclists and motorists (to varying degrees depending on the area). We have a fairly high-functioning commuter rail line with hubs of activity centered around the stations — or at least a strong potential for such. We are served by two different bus lines. We have many buildings and trees that help frame the public realm and create a sense of place. In other words, we have the makings of a neighborhood that in most places is illegal to build due to modern zoning codes. The neighborhood’s “good bones” are worth nurturing because they are what differentiate us and what will make us successful for years to come as more Americans seek out the types of vibrant, walkable communities that are in short supply. That leads me to…

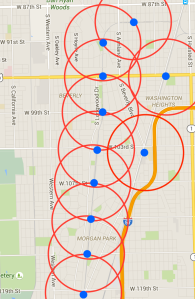

Our public transit connections. Few American cities have the type of extensive network of trains and buses that Chicago has. And on the South Side of Chicago, few neighborhoods have the abundance of transit options the 19th Ward has. We have eight Metra stations — and more if you count ones in abutting communities — where residents can hop a train that takes them downtown, in some cases, in less than 30 minutes. Each trip on Metra is one trip that isn’t being taken by car, which keeps our streets safer and encourages the kind of foot traffic that proprietors of small businesses love. Additionally, a bulk of our residents live within a 15 minute walk of a Metra station and many also within a 15 minute walk of a major bus route. That’s the type of transit network many communities in Chicago elsewhere in the United States would kill for. We have it. Every day. With better planning around it, we can make it work in our favor. I briefly mentioned it above, but I also love…

Our flora. Trees might be the most misunderstood part of a neighborhood. Used in the wrong way, such as in newly built exurban subdivisions, they are little more than “nature Band-Aids” — greenery that masks poor planning decisions in a half-hearted effort to make people feel as if they are living in a rural community. And in some cities, trees can be an afterthought, something planners feel is better left out in nature where it belongs. (Until recently, Virginia road regulations infamously referred to trees as “fixed and hazardous objects.” Buzzkill.) But trees play a vital role in neighborhood-building in part by cleaning the air and also by working in tandem with the surrounding built environment to create a strong sense of place. In our neighborhood, trees are typically more than just nature Band-Aids, and they are certainly not an afterthought. They line our streets and frame our parks. While nice to look at, they also provide a sense of enclosure and comfort, forming the walls of outdoor rooms and corridors. But they would be less effective if it weren’t for…

Our mix of uses. It’s true that I can be critical of the reluctance to build in a mixed-use fashion in our neighborhood. This is particularly true of our main streets, which would benefit from an injection of uses beyond single-story commercial buildings and parking lots. But as you wander around the neighborhood, it’s clear that putting different types of uses next to each other — or even on top of one another — was once viewed as the positive attribute it is. Take, for instance, the location of some of our most beloved institutions: Our schools and our churches. They are nestled among our homes; they are the focal points of neighborhoods. In a day and age when a new school or church is built in a far-off field to attract the maximum number of people in a sprawling region, the simple placement of an institution in the center of a community almost seems radical. But think about how your family gets to church on Sunday or how your children get to school during the week. I’m sure that in many cases walking is the preferred choice, giving families and friends the opportunity to bond over a shared activity. Elsewhere, streets and (sometimes) sidewalks just lead to these places. Here, those paths instead form an interconnected network around them, reminding us that education and spirituality aren’t just values we reflect on at specific times of the week. They are always with us. Speaking of our streets and sidewalks, I have to give a shout-out to…

Our residential streets. When we think about the state of many of our main corridors, we should look to our residential streets for inspiration. It’s clear that these streets were designed with pedestrian safety — and pleasure — in mind. Already narrow travel lanes become even narrower when cars are parked on the street. Intersections are frequent. Contrary to conventional wisdom, it’s these types of obstacles and interruptions that make streets safe. On many streets it’s next to impossible for a motorist to travel faster than about 20 mph, and often one driver has to pull to the side to allow another to pass. The design of most of our residential streets forces drivers to be alert. If our streets absolutely have to carry motor vehicle traffic this is a good way to allow it. Low traffic speeds combined with a solid if utilitarian set of sidewalks and the aforementioned mixture of uses make our side streets pleasant places to walk and bike. In cities and villages across the country, rules about engineering prevent these types of narrow, complex streets from being built today. We have them, and we are all the better for it.

In the coming year, I wish for us to…

Embrace the “urban” in “urban village.” “Urban village” is a great, catchy moniker, but I don’t know that it is always applied accurately in the case of our neighborhood. We tend to throw it around when we try to keep out elements we consider incompatible with a “village” atmosphere, such as apartments and mixed-use development, when the truth is that those very things would fall perfectly in line with a traditional village (see my earlier piece on the characteristics of a more traditional village.) As a result, we end up looking and operating more like a decentralized suburb, and there can be little to differentiate us from Evergreen Park, Oak Lawn and the like. Being an urban village also entails building on our amenities and infrastructure that are uniquely urban, such as our transit network, a hugely important piece of life in the 19th Ward that must be treated as a driver of activity, particularly around our Metra stations. We can turn to other “urban villages” for inspiration, such as the neighborhoods of Seattle, or we can look closer to home. Chicago encompasses numerous other “urban villages,” including Ukrainian Village, Roscoe Village and Andersonville, all of which more closely resemble the traditional villages we strive to be like. Perhaps the most successful one is Little Village, the vibrant Mexican-American neighborhood on the Southwest Side that was recently the subject of a very flattering photo essay in Crain’s Chicago Business. There, pedestrian-focused design, public transit, mixed uses and proximity to amenities have helped make its main thoroughfare, 26th Street, the greatest generator of sales tax revenue for the city after the mighty Magnificent Mile. A good start would be to…

Recognize that everyone is a pedestrian. At some point on most days, virtually every resident of Beverly, Morgan Park and Mount Greenwood is a pedestrian. Even those who drive to most destinations likely encounter the public realm on foot, however briefly. Knowing this, it is essential to consider how we want people interacting with the built environment as they walk from place to place. Are they more likely to have a pleasant experience navigating parking lots or passing storefronts? Will they enjoy strolling our shopping districts if they have to cross wide stroads carrying high-speed traffic or narrower corridors that tame vehicular traffic and provide safe crossings?

From this perspective, we should also consider pedestrians to be key drivers of activity and commerce and think about ways that we can enable them to move around as such. It’s easy to get lost in traffic counts and the number of vehicles per household and come to the conclusion that driving (of the high-speed, high-volume variety) must be accommodated and eased at all hours, and it might be easy to say, “Well, people just don’t walk here.” But that would be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Create an environment that fosters walking and change the game. And part of doing this requires us to…

Think of business activity as a consequence or function of a well designed neighborhood rather than a driver of revitalization. That’s a mouthful, isn’t it? But it’s something I’ve thought a lot about in the past year every time I hear about a new business moving in that residents wish was something else (i.e. a dollar store or an auto parts store) or a business that residents want to attract to the neighborhood (i.e. Trader Joe’s). Essentially, you get what you design for. While some chain/big box stores have begun adapting their exurban, auto-oriented models for older urban neighborhoods, most are looking to move to a fringe suburb where they can build cheaply, not an established neighborhood like ours with smaller buildings and lots that must be acquired through extensive negotiations with multiple owners.

However, many parts of our neighborhood don’t fit the model for smaller businesses and start-ups, either. The stroad environments of Western Avenue and the like, in their current state, don’t really lend themselves to the foot traffic that small and specialty businesses thrive on. In other words, I’m not really surprised that a dollar store filled the former Ace Hardware building on Western Avenue in Morgan Park as opposed to something more “desireable.” (For the record, I have no problem with a dollar store moving in.) The built environment along that stretch of road is like economic purgatory: Too auto-oriented and too large a space to be attractive to a smaller business yet too fine-grained to draw large national chains. At the same time, it would serve us well to not think about “scoring” certain types of businesses in hopes that their mere presence will trickle down to the surrounding area. Borders may have been a nice place to hang out while it existed — a so-called “third-place” for neighborhood residents — but it didn’t exactly turn 95th Street into the next State Street.

Instead, we should think about what makes for an attractive, well functioning neighborhood and take inexpensive, incremental steps toward creating it. Let’s look to a wonderful example in Lakeview: Business and property owners around Lincoln and Wellington avenues voted to impose a slight tax on themselves to fund street markings designed to calm unruly vehicle traffic and make the area more attractive for pedestrians. This is a fantastic example, because it is incremental. Right now, the project is in the pilot stage. Maybe it’s tweaked before it becomes permanent; maybe it doesn’t become permanent at all. But it allows for people to experience the change firsthand, while an innovative funding mechanism helps add value at a minimal cost. Let’s follow this lead and work to make our neighborhood attractive to people and businesses, because they will take notice. And as we become more attractive, we will hopefully…

Get more — and different — residents. Right now, we do a great job of attracting families, particularly those who want and can afford a detached house. It’s mostly what we offer, and a detached, single-family house isn’t a bad thing. But we are also missing out on other types of people who can help our business districts and institutions thrive, from single, young professionals not yet ready to take the plunge and buy a house but looking for a smaller apartment near public transportation to get them to their job downtown, to empty-nesters and retirees who want to sell the large house where they raised three kids but also stay in their longtime neighborhood. (Bonus: Both of these demographics have disposable income to spend at local businesses.) We have ample room to accommodate apartments, condos, live-work spaces and other housing types that aren’t single family homes along our main corridors and near our transit hubs. (You can read more about this issue, often described as the “missing middle,” as it concerns housing options that fall on the spectrum between single-family homes and large apartment towers, at the excellent City Observatory.) This helps diversify our population, add pedestrians to our sidewalks and create walkable, mixed-use environments without drastically altering the character of our neighborhood. By diversifying our housing options, we open our neighborhood to people at various stages of life and provide the ability for people to cycle through different types of living arrangements accordingly — without having to move out of the neighborhood. But to truly set ourselves on a good path for the future, we have to do one thing:

Strike the phrase “That won’t work here” from our collective vocabulary. There’s a story I love from urbanism history about New York City’s West Side Highway. In the 1970s, the elevated freeway in Manhattan was in need of repairs when a truck carrying asphalt to do the work crashed through it. Suddenly, a road that carried 140,000 cars per day was closed and carmageddon was predicted. But after a brief period of traffic backups, something amazing happened: The gridlock simply disappeared. People found new ways to get around the city. Last year, reporter Peter Simek wrote a piece for his audience in Dallas, a city that was having its own freeway debates, about the New York event:

“After decades of political wrangling, in the 1990s, New York decided to tear down the West Side Highway and replace it with a boulevard. The neighborhoods formerly divided by the road boomed and blossomed.”

I can only imagine the conversations in New York at the time: “You can’t tear down a highway here — it just won’t work! Too many people rely on that road! The city can’t function without it!” I bring up this story because I routinely hear the “it won’t work here, we’re different” argument when it comes to rethinking the status quo in relation to the way our neighborhood is designed. And to be fair, it’s not unique to our neighborhood. The status quo is familiar and change is scary. But people are pretty amazing creatures. They adapt very well when faced with changes, and often they like the new arrangement because it brings opportunities that previously eluded them.

So if we, say, put Western Avenue on a road diet, would the neighborhood collapse? If we put mixed use buildings on the parking lots near the 95th Street train station, would chaos ensue? At first, I can bet that things would be a little hairy as people worked to navigate the new arrangement. But I have no doubt our future would be brighter as a result.

[…] Urban Planning Features of Beverly to Be Thankful For (Main Street Beverly) […]

LikeLike

[…] In Beverly, Everyone is a Pedestrian, and Other Neighborhood Urbanism Hopes for 2016 […]

LikeLike

[…] Beverly Hipster Wants To Turn Western Avenue From A Vital 4-Lane Traffic Artery Into A 2-Lane Parking Lot – Main Street Beverly […]

LikeLike